“I live my life in growing orbits

which move out over the things of the world.

Perhaps I can never achieve the last,

but that will be my attempt.

Perhaps I can never achieve the last,

but that will be my attempt.

I am circling around God, around the ancient tower,

and I have been circling for a thousand years,

and I still don’t know if I am a falcon, or a storm,

or a great song.”

and I have been circling for a thousand years,

and I still don’t know if I am a falcon, or a storm,

or a great song.”

~ Rainer Maria Rilke

Let’s be honest here. Durable and devoted love has become a rare commodity.

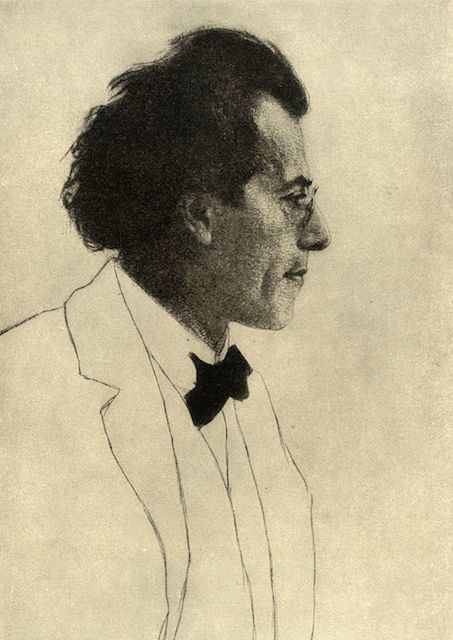

In 1910, Gustav Mahler was a tormented man. His considerably younger and “beguiling” wife of nine years and the mother of his children was an incorrigible flirt.

Alma Mahler had imperiled the couple’s marriage by carrying on an affair with a younger man in a story not radically different or less dramatic than Anna Karenina.

This is the backdrop of his Adagio for his unfinished Symphony No. 10.

Mahler was so distraught he is said to have told his wife that if she had left him “he would simply have gone out like a torch deprived of air.”

Riddled throughout the score of No. 10 are manic exclamations of an enduring love:“To live for you and die for you, Almachi!” he writes on one page.

In this age of “isms”—feminism, chauvinism, sexism, narcissism, all of which might very well apply to Mahler’s predicament and temperament—I’m afraid it would be very easy to diagnose the Maestro with OCD, or paranoia, or 100 other things.

This brings me to my most salient point.

I hate to break it to you—especially my dear brothers—but you can and will be replaced if you do not “pack the gear and keep up the rear.” That means you must have your sh*t together and be prepared to play a fair number of roles at any given time, and without warning. Being a man today is much aligned with improvisational theater. Men are now expected to navigate a world finally ready to accept the ascendancy of female power—albeit at a pace unknown. (Notice I did not say femininity, which is sorely lacking though still demanding that the ghost of it be fed.)

Men should understand every nuance, every slight variance of “ism” that stands in firm opposition to what is organic manhood—and I do mean gay, straight, and everything in-between that is “masculine.” We should be ready to vacillate between the sensitive yoga guy ready to cook up vegan crepes and a lumberjack at the drop of a hat, or more accurately at the drop of a pair of undies—be they our own or someone else’s. We should discuss equal partnership with alacrity and calmness and then pick up the check. We should detect when our partners are receptive, and we should do with the grace of a tantric masseuse.

The point of this piece is not to lament the fate of men nor justify behaviors that do not suit gentlemen—to do so would be to deny that we collectively created our predicament to begin with. Rather, I’m concerned with loss of something else of equal, if not greater, importance—namely the sensitivity of men, the soul of men, which is a beautifully devoted engine regardless of its often awkward and thwarted expression. I am afraid the heart of the American man is so easily overlooked—so quickly run under the “isms”—that innate heroism is now an overlooked and uncommon thing.

The soul of man thrives somewhat more productively in an atmosphere of receptivity. And yet, how many of us ask for warmth, kindness, and civility?

My reasoning is easily understandable. While we are busy throwing around words like chauvinism, sexism, and narcissism with greater liberality and less accuracy, we are losing sight of the dynamic nature of our gender and replacing it with bland and categorical denominations.

Yes, all manner of sh*tty male behavior exists—we know this. However, if we want men to evolve then women must evolve along with us. No expected role behavior can be foisted on a man—consciously or unconsciously—there can be no default mode of relationship whereby a woman asks or even demands that the man suit whatever method of empowerment she presently employs.

In his time, Mahler composed what is one of the most exquisite pieces of orchestral music ever written, and he did so without the burden of being chastised for it—he did so heroically. We all might consider dropping the psychodynamic verbiage and listening to what music there is between us.

I pray we do, because I am exhausted by the poor language of the modern relationship and exasperated by our common lack of love.

Author: Lois D. LoPraeste

No comments:

Post a Comment