How to Build a Mother Culture.

get elephant's newsletter

get elephant's newsletterMy daughter recently came home from middle school feeling slighted.

She’d been eating lunch with a friend when a third girl approached the table.

“Oh, she’s eating lunch with you?” the newcomer said, nodding to my daughter. “Nevermind then. I’ll sit somewhere else.”

As my daughter recounted this, her eyes welling with tears, I naturally felt protective, if not also reactive. But I knew that as a motherless mother of an only child, and a woman who has spent her whole life lacking what I call a “mother culture,” I had to think my reaction through.

The anti-bullying theme was still rattling in my head from the last Parent Council meeting, but was this incident bullying, or just one kid showing an honest dislike for another?

Sometimes people have chemistry and sometimes they don’t—and kids not only have the courage to speak their minds, they usually can’t help it. Do I shrug off the incident and let my daughter toughen up? Empower her with a witticism to use next go around? Or was I being too lax?

I thought better to check in with my go-to person, Kim.

A word about my bestie: Kim is one of those master moms who seem to have the answer at all times. Right or wrong as those answers may be, her confident delivery of them summons to mind The Oracle from “The Matrix.” Three kids and two marriages have wizened her, as well as a hard knock childhood in the deep south of Georgia, and 20-plus years in therapy.

Kim also fancies herself a novice spirit medium, and not just for the ghosts inhabiting the real estate she sells, but for my deceased mother, Joan.

“She visited me last night,” Kim might text me at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday. Or “Joan’s here.” Later, over coffee or green drinks and a walk with our dogs on the beach, Kim will extrapolate: “Joan’s proud of you.”

There’s some maternal congruence in that Kim is tall and blonde like my mother was, and that she understands what little I remember about my mother’s personality, but I haven’t exactly worked that through yet.

I used to think their similarities had something to do with my mother’s motive for contacting Kim—maybe my mother felt a kinship. Though, why go through a middleman at all?

Kim’s answer: “She comes to me because she knows you won’t be able to handle it.” And The Oracle has once again spoken.

It’s true, I can’t handle the ghost thing. In my 20s, I made the mistake of watching the movie “The Ring,” and its dark imagery ruined my dreams for a decade.

So while my daughter awaited her answer—I’d left her with a hug, her homework, and, “Let me think about the best way to handle this”—I went to the living room and dialed Kim by number and not by speed dial, as I prefer for some reason.

As the phone began to ring, I pulled it from my ear to set it on speaker when I noticed that the screen read:

Mom. Calling mobile.

What on earth?

Panicked, I hit the red button and ended the call, then threw the device—as if it were radioactive—onto the couch cushions.

I was not ready to talk to my deceased mother. Or at least, I needed some warning time to prepare. After all, I had 40 years’ worth of questions, starting with where was she. Heaven? Hell? Or that alternate plane of existence she once told me about as a child?

And why now? Why suddenly contact me directly about this infinitesimal problem with my daughter, over all others.

What about all those times I’d solicited her help by praying to her—when I longed for her and that mother culture I’d felt so lost without. When I’d wanted to know if I really had to wear black to a funeral, if I should major in English or Law, invite so and so to the wedding, add egg to falafel mix, take the epidural or go natural.

But most pressing was how exactly was she doing it?

My brain went to work quickly, synapses firing off from one stem cell to another, and when the electrical fireworks had finished, an answer began to form, beginning with a vague flashback of my setting up my daughter’s iPad so that she could text me, as well as my daughter’s insistence on being the one to type in my phone number—so it would make sense that she wouldn’t type my name as the contact for me; she would type “Mom.”

Or as my husband, who does not believe in mediums and who happened to be walking by as I was freaking out in the living room, put it more simply:

“So you basically dialed yourself.”

It took a moment for that to sink in, and to recover from my dopiness. And when I finally came to, I realized that maybe there was an actual significance to what had happened.

I sat down on the living room couch electrified by the concept. Had I unconsciously dialed myself because deep down, I finally believed that I had the answer?

That fear in my gut—the one I’d wrestled with since the moment I’d given birth, the fear that I’d make all the wrong choices, and say all the wrong things—was undetectable.

I’d spent my whole adult life looking elsewhere for the answers, trying to cobble together the right tools in my motherless tool shed. Had I finally completed the toolbox?

I thought about being 20 and going through a bad breakup, the day that a girlfriend, seeing my destructive behavior gave me my first tool when she’d said to me: “Be kind to yourself.”

It was a small, nothing comment that could have easily bounced off, but it penetrated through, and I remember thinking that there was something to this notion of self-care. And so I found my first tool as I remembered to balance partying and adventure with staying in bed, shrouding myself in soft clothes, and eating savory foods—the tool of physically caring for myself.

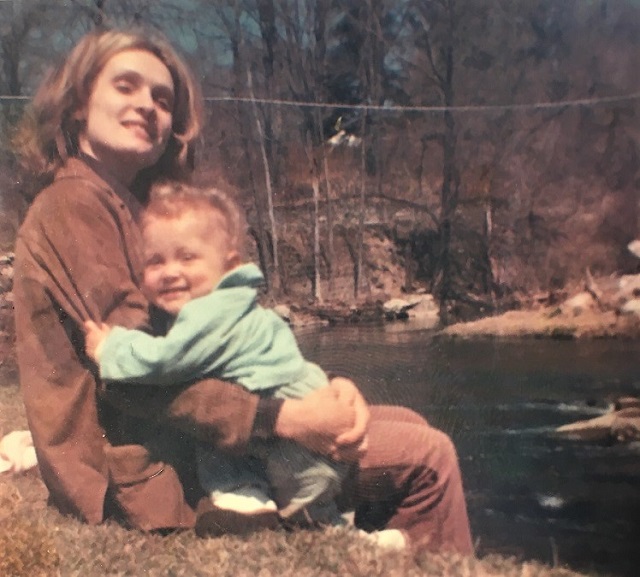

The emotional self-care would take longer. One day, after a volatile breakup, a clue about tool number two emerged: I had to love myself. The how was the tricky part. Sifting through old pictures at some point in my late 20s, I found an old photograph to help me.

The picture was of my 13-year-old, virgin self, hunched over a bowl of take-out Wonton soup, egg roll extra crispy at her side, wearing a sweatshirt and pajama pants in all her unblemished innocence. And it swelled something inside of me; made me want to reach out and hug this girl in the picture the way I imagined my mother might have done. I looked in the mirror, and knew that I had to figure out a way to see my older, blemished self with the same level of unconditional love I felt for this child self.

I couldn’t right away, but I found that I could do for her and look out for her—for myself. And so I learned tool number three: to advocate for my own happiness.

Tool number four: I learned to keep my commitments, not just because I was a grown up, but because I should care about my success in relationships and work.

Tool number five: On those darker days, when I still longed for an all-knowing maternal figure in my life, I remembered to re-read works by my favorite female authors—or turn to Mother Google. (Pre-2001, motherless daughters had it way harder.)

Tool number six: I learned how not to be a good girl, but an assertive and direct person, understanding that I don’t always have to be nice to strangers, especially men who give me the heebie jeebies.

Tool number seven: I learned the hard way that I should never gossip, no matter how great the temptation, because it will only make me look bad. That said, I needed to remind myself not to be the a-hole at the party preaching to people about not gossiping, but rather, look for a graceful way to edge out of the situation.

Tool number eight: I learned to assert my independence as a person, within the roles of wife and mother. And to keep some financial independence too. Not just the emergency 50 dollars in the glove box of the car, but as much as I could manage in an account that no one, including my wonderful husband, would know about.

Tool number nine: I worked to grow my village of like-minded types—people like Kim, who not only have their own mother culture, but a neighborhood culture with answers to questions, like: When can the kids ride bikes past the corner? Is dairy necessary or evil? Should a nine-year-old be allowed on music.ly? But learning from them didn’t mean I couldn’t make my own contributions to the dialogue.

Which brought me to tool number 10: learning that the word mother is as much a verb as it is a noun. Mothering was going to be an ongoing act—for myself and my daughter—and what mattered most in the end was not having the right answers, but helping my kid feel loved and validated.

I picked up my phone from the couch and returned to my daughter, assuring her that she was extremely likeable—offering the possibility that while the girl in the lunchroom was less than perfect in her delivery, she could have been having a bad day. Who knows if someone said something unkind to her that very morning? I suggested that my daughter try to shrug it off, move on, and hope that it didn’t happen again.

But it did happen again—or something of the same variety.

This time, I called the girl’s mother.

“What did she do now?” the mother sighed into the phone, in a tone I found a confusing mix of sarcasm and confrontation.

Apparently I’d missed the most recent Parent Council meeting in which it was discussed that the very last person you should contact is the other child’s parent. Instead, one should first go to a teacher or administrator.

After much sighing and complaining about girls being impossible and who’s mean to whom at the school, the mother agreed to my suggested play date—again in that confusing tone—and without firming up a plan, rushed me off the phone. When I saw her a few days later at a Girl Scouts meeting, she rolled her eyes and tore off in another direction. This time, I counselled my daughter differently about her classmate.

“But you said—”

“I know what I said. And now I’m saying something else. Keep your distance, and if she actively pursues you, tell your teacher.”

Tool number 11: Every village will have its antagonists that go against the very culture you are trying to create. The good news is that they will push you to grow.

Author: Heather Siegel

No comments:

Post a Comment