The first year I was married, I did my annual, month-long meditation retreat.

Like all retreats, it had its difficulties, but overall was deeply rewarding. I ended the retreat with a wonderful sense of clarity, peace, and ease as well as insight into my own psyche, as well as the dharma.

My wife picked me up from the airport, and I’d say within 5-10 minutes of being in the car together all that peace and insight evaporated. I felt defensive, angry, withdrawn, and experienced a whole lot of other painful emotional states as we continued to fight for at least two days. I can remember lying on the couch, totally overcome, wondering, “What happened to all that ease and insight?”

Ram Dass once said, “If you think you’re enlightened go spend the weekend with your family.” The next year, I did just that. I went on my annual retreat, only this time I returned to my wife and my parents, who had rented a beach house together. Within about a day, I moved from equanimity to emotional overwhelm.

So what happened? Why didn’t all of that wakefulness and well-being I experienced in my retreat seem to translate into my daily life? Sure, maybe it’s just me. Maybe other people are navigating this transition from the cushion to everyday life with more grace. But looking around, I saw many of my peers, all serious practitioners, struggling with behavioral, interpersonal, and emotional issues off the cushion as well.

I also see echoes of this tension with really great meditation teachers—often deeply realized practitioners—who, on the more harmless side, seem arrogant or emotionally immature and on the more harmful side get caught acting in ways that are deeply at odds with the values and ethics of their own teachings: sleeping with students, taking drugs, getting tangled up with money and power.

So again, what’s going on here?

Ken Wilber provides a potentially helpful model for making sense of this dynamic. Basically, he says “waking up” and “cleaning up” are different developmental trajectories. You can, for example, have someone who is awakened to the fundamental nature of self and reality—or in more Buddhist terms, awake to impermanence, dissatisfaction, and no-self—yet because they haven’t dealt with their shadow material they really haven’t cleaned up. All that illumination, in other words, passes through a broken personality.

So my answer to the question of “what’s going on” is that meditation practice works really well for waking up but doesn’t seem to help much with cleaning up. The reason is because meditation practice is about unifying all the disparate parts of the mind, thereby making it a powerful instrument for waking up. But in order to clean up, we need to be in dialogue with all of these various parts of ourselves.

Meditation, Unification, and Waking Up [1]

When I say meditation, I’m talking about the systematic training of the mind outlined in the book I wrote with John Yates, The Mind Illuminated. Drawn from a variety of traditional and contemporary sources, this is a stage-based approach to meditation in which at each stage you’re working on specific mental skills and progressively gaining more advanced abilities. This developmental movement through the stages can be described as unification of the mind.

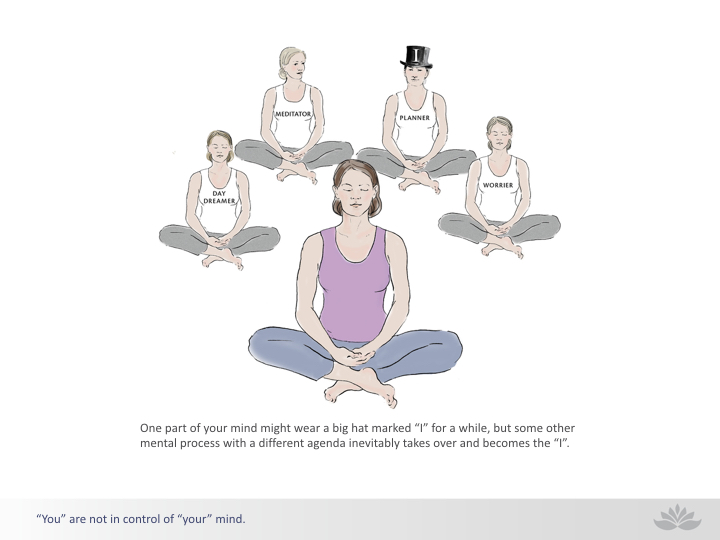

The idea of unification rests on the claim that who we are is many. Another way to say this is, there is no singular, stable self but lots of different “selves.” Unifying the mind means bringing all of the parts of ourselves, what we call sub-minds in the book, around a singular intention—in this case, to meditate.

The idea that we have many, often conflicting, parts shouldn’t come as a surprise to readers raised in a therapeutic culture. This was a central insight of Freud’s ego, superego, and id model of mind, as well as Jung’s notion of “complexes.” Subpersonalities is another way that various schools of psychotherapy refer to our inner multitude.

But you don’t need to know or go to therapy to discover this assembly. Just sit down to meditate and follow the simple instructions to close your eyes and keep your attention on your breath. What most people quickly discover is how difficult this totally simple task really is. One part of your mind might have the intention to meditate, but pretty quickly other parts of the mind begin planning, worrying, fantasizing, remembering, and on and on.

It’s often so chaotic that people who are just beginning to meditate think that meditation is creating the problem. In actuality, they’re seeing what’s happening in the mind for the first time. In a sense, the mind has a mind of its own—or more accurately, the mind has a bunch of minds of its own.

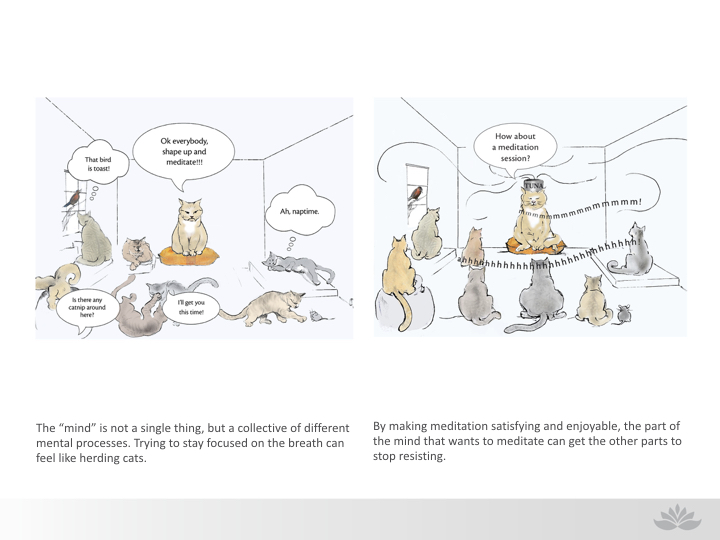

Think of it this way: our minds are like a room full of cats.

One cat (sub-mind) wants to meditate, but the other cats are more interested in sleeping, catching birds, getting high on catnip, playing, and so on. Unifying the mind means getting all those cats (parts of the mind) on board with the intention to meditate.

This isn’t going to happen through force or will power, as the first image reveals. Instead, it’s critically important to find any aspect of the practice that is enjoyable or pleasurable, especially as you first begin to develop a meditation practice. People who follow a stage-based approach like this discover that their meditation will become more pleasurable and the mind naturally more unified.

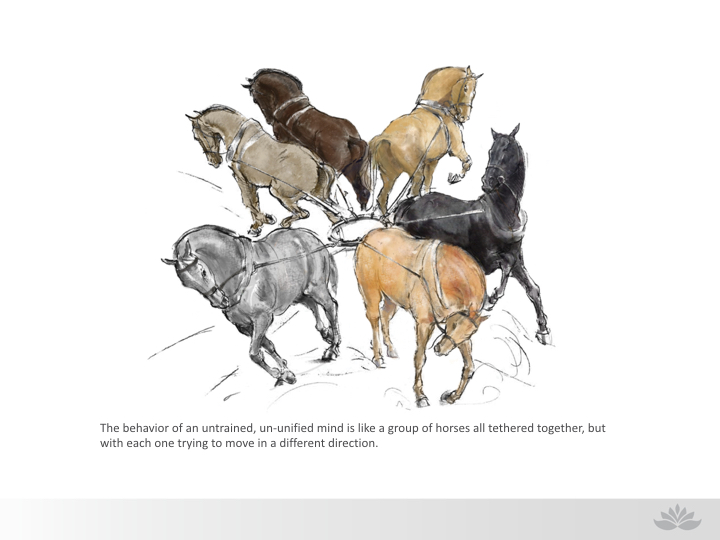

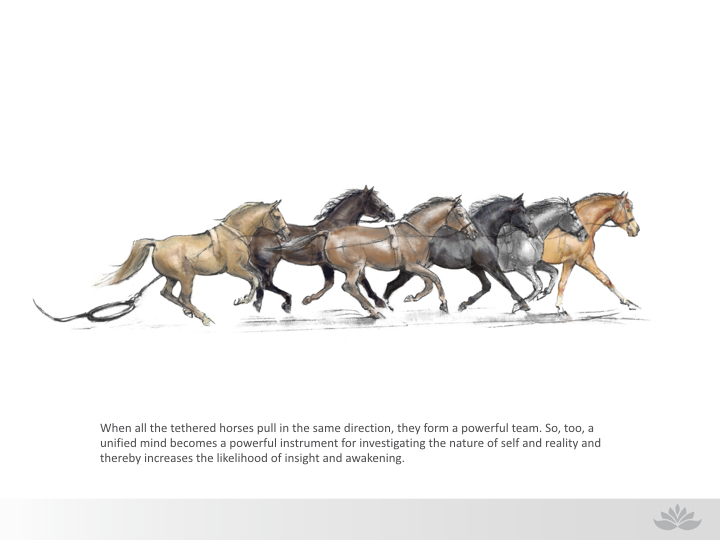

One more useful animal analogy is to compare the untrained, un-unified mind to a group of tethered horses all pulling in different directions.

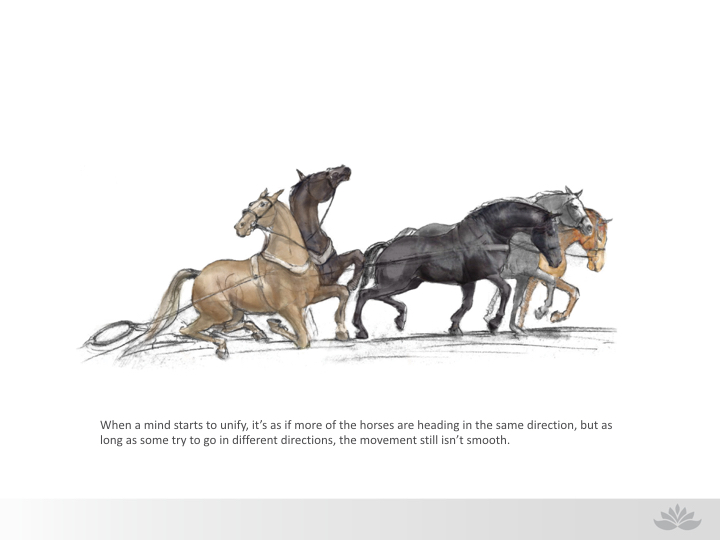

Through training and diligent practice, more of the horses begin to head in the same direction until, eventually, they are all powerfully unified

Similarly, a fully unified mind is a profound and powerful mental state. In Buddhism, it’s called samatha and comes with five qualities: effortless stable attention, powerful mindfulness, pleasure, tranquility, and equanimity.

In essence, this is an optimal flow state or an experience of being “in the zone,” where the various parts of ourselves are powerfully consolidated around a single intention. The point of this state, however, is not for itself. Instead, a mind in samatha is in ideal mental shape to practice vipassana, or insight. It’s like having a powerful instrument to investigate and penetrate the existential marks of existence—impermanence, no self, and suffering.

So how could such a powerfully unified mind not help us clean up? Especially considering that the entire process of unifying the mind requires a kind of mental excavation and purification where we increasingly see more and more of the hidden, rejected, emotionally laden parts of ourselves and our histories.

The reason is because of the common meditation advice we often receive—just let it go.

Or, as we say in The Mind Illuminated, whatever arises let it come into awareness (don’t resist it), let it be there (no need to engage it or push it out), and when it’s ready, it will simply go. Our task is simply to be non-judgmentally mindful of any and all material that surfaces. We’re not advised to analyze the content or get involved with the different parts of ourselves that might emerge, or their emotional weight. Instead, we’re learning to see everything as it is—arising and passing phenomena.

This is perfect advice for waking up.

For cleaning up, however, mindful observation of passing emotions and thoughts doesn’t seem to be enough. That’s because many of these parts, especially the more troublesome ones, simply become quiet due to unification or they slink off into deeper recesses of the unconscious. Then when we’re off the cushion and the mind becomes less unified, they come out of their slumber and wreak all sorts of havoc. Put it this way: meditation can become a powerful tool for bypassing these parts of ourselves. Ironically, the more skillful and advanced our meditation practice, the greater the opportunity for bypassing these various characters.

Dialogue and Cleaning Up [2]

Cleaning up requires that we do more than just letting these parts of ourselves mindfully come and go. It requires that we welcome and engage with them. In other words, cleaning up requires active dialogue with those rejected and dejected parts of ourselves with the goal of reintegrating them into the fullness of ourselves.

So what does this dialogue look like? It can look a lot of ways, but let me give you some of the basic elements. The first is invitation—inviting everyone into the light of conscious awareness. In The Mind Illuminated, we spoke about conscious awareness as being like a corporate boardroom, a useful image for waking up but for cleaning up it’s simply too cold and calculated.

For dialogue, I prefer thinking about conscious awareness as a campfire circle where everyone is welcome. In particular, those parts that are hiding in the shadows, the ones that have been subtly or overtly excluded from the full warming light of consciousness.

Without this invitation, those shadowy figures remain on the margins, out of sight but in no way out of mind. Again these more ignored parts of us can create serious problems when they are triggered, taking over how we think, feel, and behave.

Jung talked about this hijacking of the psyche as being overrun by complexes: “Everyone knows nowadays that people ‘have complexes.’ What is not so well-known, though far more important theoretically, is that complexes can have us.” Sometimes we’re aware of being hijacked, very often we’re not. Sometimes getting hijacked can be dramatic, like an ogre rampaging out of the dark and taking over the light of conscious awareness, and other times much more subtle, like a delinquent child shooting spitballs from the shadows.

So dialogue begins with an invitation, and doing so with an attitude of acceptance is the second element. That means recognizing that every part of ourselves, no matter how seemingly reprehensible or shameful, repulsive or childish, serves a purpose in our personal history—to get some need met, to provide for our safety or well-being in one way or another. We often don’t know the purpose of a particular sub-personality. But that’s the whole point of starting a dialogue—to find out.

Then there’s the actual dialogue. This can be done in all sorts of ways, such as journaling or just talking to ourselves. I prefer to visualize inviting those sub-minds around the fire to sit and talk. The phrase I like is “tell me more.” Tell me about yourself, what is it you want? What are you afraid of? What do you need? Tell me more.

Another good question is, how old are you? That’s because each of these parts of ourselves developed at a certain point in our personal history. For instance, as a child we may have discovered the best way to ensure our safety was to please our parents. Repeated enough because it works, we develop a “pleaser” sub-personality. That’s not a problem—it’s an age appropriate strategy for a child. But as an adult, trying to please everybody is a recipe for disaster.

Dialogue can be subtle work and often we try to coerce an answer. But patience is key, always inviting and welcoming with gentle questions: “Who is there?” “Who wants to speak?” It’s about listening, not forcing a conversation, welcoming all the parts of ourselves with genuine acceptance and curiosity.

Another critical piece in this dialogue work is other people. By ourselves, we can remain pretty blind to these various parts of ourselves, but they often emerge in relationship with others. In other words, other people often trigger various sub-minds we’d rather not see. This makes sense considering that many of these parts of ourselves developed in interaction with others; they’re the internalization of external relationships.

This is probably one of the reasons why, after a long meditation retreat of silence and solitude, I came home and had a total meltdown. It’s because in the cloistered retreat environment I was buffered from most social interactions and therefore buffered from dealing with those parts of myself that are triggered by others. If only I could have stayed in retreat, I could have maintained my illuminated state and kept all my shadowy parts at bay.

This may also be one reason why supposed enlightened masters can behave so badly. They may have unified minds, but they can also use these unified minds to bypass their shadows. This gets more pronounced if they are surrounded by devoted followers that never challenge them. Without this kind of challenge and other more typical social interactions, they may not see or have to confront certain problematic aspects of themselves. When challenges are leveled at the teacher, they’re usually dismissed and the challenger marginalized or pushed out of the community. In this sense, the community is like the campfire of collective consciousness, but rather than inviting in the challenger, dialoguing with them so that not just the teacher but the whole community can clean up, they’re pushed into the shadows.

Reactivity to others can also help us see our shadowy characters. Any time we’re reactive, we’ve likely been hijacked by some part of our mind. So reactivity toward others can be a gateway to discovery and dialogue. It’s true that mindfulness is all about becoming aware of our reactivity, pausing, and then letting it go. But for cleaning up, we shouldn’t just let it go, but instead ask, “Who is this?”

And of course, dialogue with other people is essential for helping us discover and work with these parts of ourselves. Silence and solitude for honing and unifying the mind is perfect for waking up. But dialoguing with others—authentic dialogue—is what will help us clean up. This is the basis of many current psychotherapeutic models.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying dialogue is more important than unification or vice versa. I’m not saying cleaning up is more important than waking up or vice versa. I am saying that we’ve got two related but distinct tasks that require different sets of techniques and intention.

Meditation and waking up is not a magic pill that will cure all your problems and save your life. The truth is that there might not be any magic pills for creatures such as ourselves, who are complex and multifaceted, paradoxical and mysterious.

~

[1] All images are from The Mind Illuminated: A Complete Meditation Guide Integrating Buddhist Wisdom and Brain Science for Greater Mindfulness, Atria Books, 2017.

[2] Much of my thinking and practice around dialogue comes from Kemp Battle, a brilliant man and good friend.

~

No comments:

Post a Comment