“I study Confucius to learn how to rule the world, I study Taoism to learn how to live in it, and I study Buddhism to learn how to leave it.” ~ Seng Chau

I discovered meditation’s true purpose quite unexpectedly, from a down-to-earth carpenter living in a monastery in San Francisco.

I was fresh from a two-year stint in India and Nepal in which I was meditating all day, living in caves and monasteries. I was quite full of myself as a yogi and meditation master.

Shortly after my arrival at Gold Mountain Monastery, I went into the woodworking room to sand a food bowl I had made, where I encountered a man named Allen working on a chair for the Master.

I hadn’t met Allen before, but without any introduction, I asked him, “Why are you here?”

His reply shattered my self-image and made me realize I knew nothing about meditation. He said: “I am here to end birth and death.”

As a side-note, now, 45 years later, Allen is still there in the monastery compound, married and engaged in meditation and monastic activities.

Allen’s words moved me deeply. Although I had been sitting in meditation at least 12 hours a day for the past two years, I hadn’t realized my motivation was one that would never lead to liberation.

I was on a meditation ego trip and didn’t even recognize it.

Allen’s words were spoken so matter of factly and from such deep conviction that I was moved and shocked out of my spiritual naïveté. His words were to shape my next 40 years of spiritual inquiry.

When we practice buddhadharma, or the path of Buddhism, we inevitably collide with our own desires and attachments.

It is a path of letting go and making room for the new. It entails a willingness to relinquish many sources of pleasure to gain a little bit of truth.

Meditation is not about “getting on in the world.” On the contrary, it is a commitment to undermining any attachment to the world—or ourselves, or ideas of ourselves, for that matter.

While the period we actually sit in meditation may be only 15 minutes or so a day, everything we do outside of that hour must be supportive of the practice. It should be obvious, but the fact that meditation entails a lifestyle change that focuses on undermining desire and attachment is not apparent to most engaged in modern meditation. Not to mention meditation teachers governed by monetary interests, but even authentic Masters often shy away from this point of relinquishment in fear of losing their audience.

As far as attachments go, the sutras teach us that desire for food and sex are the primary reasons for rebirth. Now, we don’t have to be celibate and we don’t have to eat once a day, but we do have to examine our own mind and ask ourselves if, during meditation, we are distracted by thoughts of food or sex or both, and if so reign in what needs to be reined in.

More importantly, aside from the universal attachments mentioned above, there are individual attachments unique to each of us, and it is these that distract us most during meditation—and even undermine any inclination to meditate at all.

There is nothing intrinsically “bad,” whether it be money, delicious burgers, fancy clothes, an enviable car, an upscale house, and so forth. All these things are okay in and of themselves—but we can and do make them not okay by our attitude toward them.

One person can drive a Ferrari and think nothing of it, while another can become so full of himself that he can barely pay attention behind the wheel. As far as attachment goes, it is a personal matter that each of us must come to terms with by examining our own attitudes—without bias.

Generally, we meditate to achieve selflessness, which is an enormous topic. Suffice it here to say, it means getting rid of our attachment to ego so we can be who we are without any trappings.

Whatever it is that puffs up our ego should have numbered days.

We don’t have to knock off our attachments all at once, but they should at least be in our sights.

Non-attachment is not about having few things. A beggar attached to his rags, selfishly hoarding a few morsels, fails no less than a rich man attached to his wealth.

Attachment is not about what we have, but how we identify with it.

In my youth, I had been meditating for my own personal ambitions. I identified with the lifestyle that I perceived to be cool and desirable. I felt that my practice elevated me above my peers who didn’t meditate.

Though I had few material attachments, I was attached to my self-image. This is an even bigger obstacle than a material one, and far more difficult to renounce.

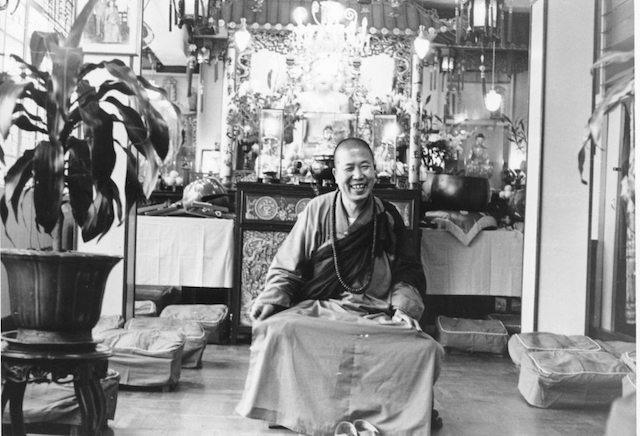

Ending birth and death was something I never thought about. But, Allen’s words were in accord with the Dharma, and they struck a chord in my being. I realized I had to get serious about what I was doing, and I soon committed myself to stay with Allen’s teacher, Manchurian Master Hsuan Hua, for 10 years.

I became a monk, and made a lifelong commitment to undermining all of my attachments.

After my time at the monastery, I married and had children in Nepal. Although I am no longer a monastic, I have not forgotten that meditation’s purpose is to end cyclic existence, not embrace it and forever spin on the wheel of birth and death—samsara.

The modern mindfulness movement would have us all remain naïve to meditation’s larger enterprise.

With some exceptions, most notably our accomplished Tibetan Masters and a sprinkling from other cultures, few of today’s mindfulness and/or meditation teachers ever talk about ending cyclic existence in samsara.

But the larger problem is that even if their audience wanted something more, they would be impotent and unable to satisfy their wishes because they themselves have not been truly introduced to the nature of the mind and undergone the years of discipline such instruction entails.

If we don’t know better, that is okay—we are not expected to. But it is our responsibility to seek out masters who do know better.

We must seek teachers with lineage and authority, who don’t mix dollars and Dharma, and have genuine compassion.

If we are to practice meditation, we should enlighten ourselves to what the path really entails and what it aims to accomplish.

Cyclic existence, ending the cycle of birth and death, or resolving all of our karma, is a big project and not one to ignore if we are to taste the sweetness of the Dharma.

We are not children needing to be spoon-fed, and if instructors are not telling it like it is, it is our responsibility to ourselves to study authentic commentaries.

If we keep at it, as the saying goes, “When the student is ready, the Master appears.”

It worked for me, and can work for you, too.

Author: Richard Josephson

No comments:

Post a Comment