A friend handed me a book.

I stared at the cover, as if given a genie in a bottle. Could this book, single-handedly, have the answers to the burning questions my soul pondered, asked, and screamed to the universe for the last four years?

My best friend, Lori, completed suicide on the night of Friday, October 15, 2015. The emotional landslide, physical torment, and spiritual questioning her actions caused her children and me has had an ongoing impact on all our lives.

Every single day, someone like me goes from being a best friend or a parent or a spouse or a partner to being classified as a “loss survivor.” According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, on average, there are 129 suicides per day. Every. Single. Day.

I always felt like I did not have the education or experience, at the time, to fully help Lori. I did what I could, but for years I felt like that wasn’t enough—until my friend handed me this book, Why People Die by Suicide, by Dr. Thomas Joiner. The pages have coffee stains and sticky notes marking statistics and revelations. From my experiences, combined with this book, these are things I wish someone would have helped me with sooner.

1. There’s no shame in the truth.

I’ve found that speaking about my loss, or about people with depression or suicidal thoughts, makes other people uncomfortable. It is taboo to speak of unhappiness. My Facebook friends should be plentiful, my Instagram account should be filled with exotic vacations, and my Twitter feed should be filled with 140 characters that convince the rest of the world that everything is perfect.

I’ve found that speaking about my loss, or about people with depression or suicidal thoughts, makes other people uncomfortable. It is taboo to speak of unhappiness. My Facebook friends should be plentiful, my Instagram account should be filled with exotic vacations, and my Twitter feed should be filled with 140 characters that convince the rest of the world that everything is perfect.

But we all know that everyone is fighting some kind of battle behind closed doors. When it comes to suicide, the truth is painful and not perfect.

There is an acceptance that our loved one was sad, lost, and burdened. There is a fear that someone may point fingers or pass judgment. According to Dr. Joiner’s research, “44% of those bereaved by suicide had lied to some extent about the cause of death, whereas, none of those dying from accidents or natural causes lied.”

Those who are left behind have difficulty even saying the word “suicide.” While our generation is seeing a shift in topics of self-care, it is a slow-moving shift, and loss survivors often have a multitude of facts to face. We must provide them with space and grace to accept and own the details of their story. And when they speak about their truth, that is a level of intimacy that should be praised—not shamed into silence.

2. We are doing (did) our very best.

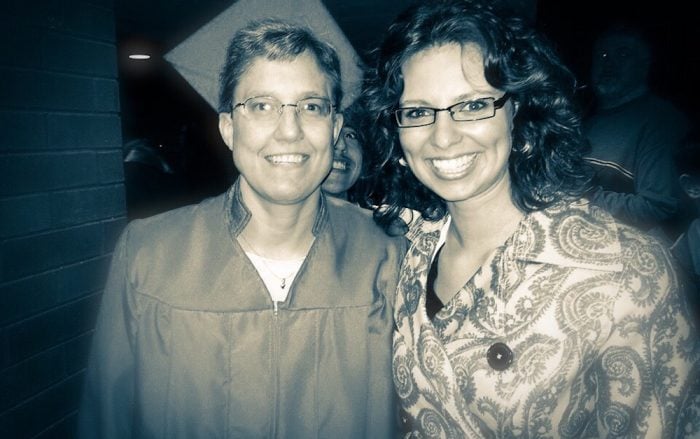

The night that Lori graduated from college was bittersweet. As an adult, with a full-time job and a family depending on her, she constantly second-guessed whether spending time and money on her education was selfish. It did not matter how much I encouraged her or how often her children praised her for her 4.0 GPA—she felt undeserving and unsupported by others in her life.

The night that Lori graduated from college was bittersweet. As an adult, with a full-time job and a family depending on her, she constantly second-guessed whether spending time and money on her education was selfish. It did not matter how much I encouraged her or how often her children praised her for her 4.0 GPA—she felt undeserving and unsupported by others in her life.

There was a dark cloud that had taken over Lori for the better part of two weeks leading up to the graduation. Following the ceremony, Lori’s family and friends took her out to eat and celebrate. We all laughed and shared stories, but Lori was silent. She quietly leaned over and said to me, “This is the last place I want to be. I can’t breathe."

She was having a panic attack, and I knew the symptoms were only going to get worse. Semesters of uncertainty and little support from the very people sitting at this table were wreaking havoc in her head. She was replaying their conversations about what a waste of time and money it was to get a degree. Her face was red, and she was sweating. I looked her in the eye and said, “We are staying. Food is on its way. Do you want me to tell you stories?” With tears in her eyes, she nodded “Yes.”

For Lori, my incessant chatter helped to distract her. Midway through my stories about my son or the way the cats refused to use the litter box, I would pause and ask, “Are you breathing?” It would be enough of a reminder and I’d continue to talk on. Sometimes tears rolled down her cheeks during these conversations. Sometimes she was silent and emotionless. I could tell she was lost in her thoughts. She was physically sitting next to me, but her mind was somewhere else. But I knew what I had to do, and so I spoke until her breathing calmed and the dark, sad cloud passed us by.

I wasn’t a therapist. I wasn’t a counselor. Was I even helping her? I had never had a panic attack in my life and did not know what caused them or how to fix them. Was I doing this right? All these years I wondered if I had even helped her. But Dr. Joiner stated, “Some people don’t require understanding in order to act right. They just let compassion take over.” I had no PhD. but I tried to follow my heart and stop trying to understand the situation and just get her through it.

Maybe we give them a pep talk. Maybe we give them a hug. Maybe we hold their hand, as tears stream down their face. Sometimes we must be present, even if it doesn’t make sense.

Whatever our heart tells us to do is the best thing for them in that moment. And we did our best given the circumstances.

3. “Moving on” is what they want us to do.During a sunny, humid Illinois summer day, I had lunch with Lori, but she was short on time after taking a new job. We found a booth by the window with the sun beaming in on us. I started asking her questions about the job, the commute, the coworkers, and she briskly interrupted me, “I’m adulting. It’s fine. Tell me all the happy and silly details of your life. Aaaand, go!”

She beamed ear to ear hearing about happiness. She was the most selfless person I knew and had a magical skill of remembering every person and every detail of my stories. She was elated about my happiness in my relationship, she was tickled pink when I told her that my son taught the cat how to fetch. Her daughter was dating someone who we quickly realized was more than a summer fling, and we joked about Lori’s hairstyle and how it would have to change for the wedding. We talked about how her son would soon have his driver’s license and be chauffeuring her around town—but most importantly, it would provide him with a sense of freedom. And that’s when she leaned in and said, “All my people are happy, and that makes me happy.”

I believed her statement then, and I still believe it to this day: All my people are happy, and that makes me happy.

I think that Lori’s heart was made of four decades of papier-mâché burdens, broken promises, and opportunities missed. Many of the pieces were her experiences, but some of those pieces of pain she took from others so that their heart wouldn’t hurt. She collected the memories, the heartbreak, the longing, and the lack of acceptance and pieced them together to form something resembling the shape of a heart. To the outside world, I am sure her heart looked messy. I know she believed that this is what love was—taking in other people’s happiness and pain and sadness. But over time, she did not have the strength to hold the heaviness anymore.

As a loss survivor, I know that she was the happiest when her people were happy. After Lori completed suicide, we moved on with our lives by incorporating the old traditions we once enjoyed together. It has been said that “you can’t repeat the past,” and we agree, but healing looks different for everyone.

For us, taking the steps forward meant stepping out of our pain and into a hopeful future. Autumn arrives and I plan our annual pumpkin patch outing with her children. We speak of her during these outings like she is here, like she is witnessing our joy.

We share in milestones and new memories made together—like marriages, graduations, and babies. We move forward, day by day, new memory by new memory, because we know it would make her happy to see us happy together.

~

~

Slowly, over time, I have made peace with all the burdens and brokenness that Lori felt. I always wanted to fix things or help her, but I realize I couldn’t heal her. And she knew I couldn’t heal her, either. She just wanted to no longer deal with the pain, even if that meant no longer living.

With knowledge and grace, there has come an acceptance in my life.

The great American poet, memoirist, and actress Maya Angelou writes, “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” This has become my mantra and my means for helping other loss survivors and bereaved families—my motivation to move on.

AUTHOR: CASSIE YODER

IMAGE: AUTHOR'S OWN

No comments:

Post a Comment