“It is not as if what is true, right, urgent and necessary is a light, and what is harm is darkness. They are both darkness; they are both lights.” ~ Anne Boyer

~

There are only a few phrases my father has ever spoken aloud to me.

“I love you” is not one of them. “Never depend on a man” is.

And I don’t, in fact, rely on men for emotional sustenance, for income, or for praise. Sometimes, men provide these things for women, but sometimes they don’t, and I resist disappointment like a used handkerchief.

Back when we were all small, before our family fell off the ledge, my sisters and brother and I shared a bedroom in the only house we would ever own: a soon-to-be foreclosed 800-square foot shelter bordering the city dump. Back when we lived on dreams and loans, I used to rise early, when it was virtually silent, to watch my father get ready for work.

I would sit on the counter in the bathroom while he lathered his face with Noxzema, heating the water until it fogged the mirror, watching while he slid his razor across his preternatural white face. Sometimes, I would dip my fingers into the cream and softly, tentatively, quietly mold it onto my girly face.

My father tolerated this in silence, without so much as a nod. One time, when he was finished shaving, before he splashed on his Old Spice with a virulent shake, he took the blade out of the razor and handed me the empty shell. I carefully stroked my tender cheeks with the vacuous metal, until each white row had vanished and I looked like a little girl again. Then I splashed my face with water and looked to him for approval. He didn’t comment, but he held my gaze—and I felt something akin to respect. There was validation in the motions I had sequenced, almost in tandem with his, the rituals of manhood like a handshake between us.

My older sister later told me that girls don’t shave their faces, but that wasn’t of particular interest to me. Our home was a man’s world, where brute strength still ruled, and I was proud that I had stood there next to him, doing what men do. I loved watching his calm face in the mirror, as every errant hair was meticulously removed. My sisters often claimed he looked like a bear, that they were frightened of him, of his gruff manners and his guttural growl. And to be frank, I was often frightened of him myself—but not as I sat on the bathroom counter, not during his morning ritual, not while I could see my face in the mirror next to his.

It’s simpler to remember the brutality, the random anger, the tightening spine of fear. It’s simpler to negate moments like these, to dismiss early morning reflections in a mirror, to see them as the anomalies they certainly were.

And yet, I wonder now if he shared mornings like these with his own father when he was small, before his mother took him far away on a bus in the night, away from experiences he never spoke of.

My father is turning 82 this week. My sister tells me he is still strong and athletic, that he swims daily and has a mean golf swing. She says he’s still taller than everyone around him, but he doesn’t bow his head to listen—he carries himself regally, with no real expressions. She says he’s calmer with age, and he’s gentler when he blows his nose on the handkerchief he still keeps folded in his pocket.

My father was 12 when his mother executed their stealthy get-away, when the two of them rode on a bus across the entire country to forge a new home. She didn’t tell him they were leaving, so he never said goodbye to his friends or his father. Long before he could become my grandfather, my father’s father died of alcoholism and pneumonia, a man alone in his early 40s, estranged from his wife and teenage son. He made it to California, but my father didn’t know his father arrived here or that he died here—not until many years later, when he visited the military grave, long grown cold.

My father never speaks of these things.

The first boy who loved me called me a cat. His father died when we were in our early teens, and my father became his coach and mentor. We grew up together in a strange, small world. We escaped in different ways and both married and had children young, though not with each other.

He told me later, “Girl, your dad pushed me to be a man, but he just pushed you away.” He laughed, and then stopped laughing. He said that when I was pushed, sometimes from skyscraper heights, he’d seen my fear but didn’t step in to help. I’d squirm and screech and hiss and flail, but I would land on my feet. He said he grew to respect me for that.

I told him that it all sounded like a form of torture, that people shouldn’t take cats up to skyscrapers, let alone drop them off ledges. He said I could handle it, that it was my lot in this world to be brutalized—that I would survive.

During a particularly difficult juncture not long ago, he called to remind me of this. I assured him I had come to the end of my nine lives, that my luck had rampantly run out. “Ahhhh, but it’s not luck,” he assured me. “It’s in your training. It’s so well-rehearsed, it looks like instinct, but I know you and I know where you come from. Fact is, you know how to fall.”

And I have my father to thank for that.

~

AUTHOR: MICHELLE DOWD

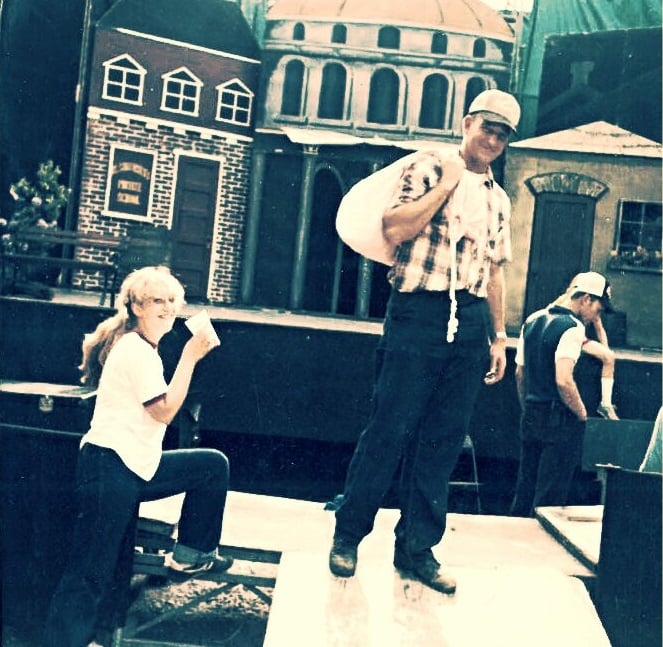

IMAGE: AUTHOR'S OWN

No comments:

Post a Comment