“For goodness sakes, you are far too nice with your mother,” my friend Julia said after I hung up the phone.

Though uttered over 20 years ago, I still hear her words echo in my head.

She had overheard the conversation I was having with my mom on the big, black rotary phone in her kitchen, where she was preparing her famous Greek rice-stuffed tomato dish. Julia had a daughter of her own, just a year older than me.

“I’ve spent many a therapy session after being raked over the coals by my daughter!” Julia lamented. “It’s not normal to be so nice with one’s mother!”

Julia was not the first to remark on my niceness. My Greek host family had levied a similar critique when I first went abroad as an exchange student to Athens at age 16. Within a few weeks of my arrival, Elsa, my younger host sister, turned to me with exasperation and said, “Stop it! You can’t go around smiling and saying ‘Hi’ to everyone you meet on the street. They’re going to think you’re crazy!”

At the time, I attributed my friendliness to being a typical Californian. I only began questioning the “normalcy” of my niceness when they pleaded with me to stop saying “thank you” for everything. Elsa told me it was annoying, and my older Greek host sister concurred: “You don’t have to say thank you all the time, especially for every meal. It’s a normal thing for my mom to cook; it doesn’t necessitate a ‘thank you’!”

It’s three decades later and I’ve still not weaned myself from saying “thank you” at every turn. And it’s only recently that I’m waking up to the fact that not only can excessive niceness be annoying, but it can be lethal.

Yes, that’s right: lethal.

A few weeks ago, I happened upon a YouTube video of a talk by Dr. Gabor Mate, author of When the Body Says No, and felt my blood go cold as I listened. In this talk, addressed to a workshop for caregivers, Mate spoke about the correlation between chronic illness and certain behavioral patterns.

He had my full attention because not only had I been the end-of-life caregiver for my friend Julia, but I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer nearly a year ago, and had spent years recovering from Guillaine-Barre Syndrome, an auto-immune disease, which struck me at age 25.

Mate maintains that people who have a chronic illness of any kind—from cancer, multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease—often fit certain personality profiles. These include paying a lot more attention to the needs of others than to their own; getting caught up in their job or role as a caregiver rather than looking after themselves; and suppressing the so-called negative emotions, such as sadness and anger. In fact, they try not to acknowledge these emotions even to themselves. And, finally, they tend to think they are responsible for how other people feel and are terrified of disappointing others who are important to them.

It is with some shame that I realize at this “mature” age that I’m still constantly fighting this demon—fearing disappointing others and feeling responsible for how they feel. In fact, the most stressful part of this past year was worrying about my loved ones’ fears and the distress I was causing them with my choice to treat the thyroid cancer non-conventionally. This was no small mountain to climb, given my mom’s background as a nurse and her conviction that opting out of surgery was the equivalent of a death sentence.

So many people talk about the fears that assault them when the big “C” word enters their life. But, as I reflect on the past year, I realize that personal fear just had no space to enter, as the room was too occupied with anxiety about others. Or maybe I’d unconsciously denied it entry, as part of the life-long pattern of being oblivious to so many of my own needs and wants, or minimizing them so as not to be a “nuisance” to others.

“The emotional patterns we learn as small children,” Mate says, “live on in the cells of our minds and come back to us as adults.” And the pattern that tends to characterize the chronically ill is an overwhelming sense of responsibility and self-suppression.

In the aforementioned book, Mate notes that extreme suppression of anger was the most noteworthy characteristic in a study of breast cancer patients in a 1974 British study. Another study by Psychology Today reports that “Extremely low anger scores have been noted in numerous studies of patients with cancer. Such low scores suggest suppression, repression, or restraint of anger. There is evidence to show that suppressed anger can be a precursor to the development of cancer, and also a factor in its progression after diagnosis.”

But self-suppression is not innate. It’s a learned coping style.

Infants automatically learn to suppress pain and stress as they sense their mother’s distress. I liken it to a Code Red that goes out in the infant’s survival program, alerting it to the possibility of over-burdening the mother and therefore risking possible reprisal or rejection. But what begins as a coping response in an infant or child becomes a source of illness in the adult.

Reflecting on my own case, I can only conjecture that a certain Code Red went off in my system and that of my twin sister in early childhood when our biological mother gave us up for adoption. She apparently kept us for five months and then we went to foster care until being adopted at 11 months. Did these early childhood circumstances contribute to the formation of this excessive niceness and people-pleasing as a coping strategy? Though the impact of that first year of life is unknown, what I do know is that my sister and I were raised in a context, like so many, where anger was not allowed.

Anger was the prerogative of parents (in which my dad had the monopoly), and not the prerogative of obedient, nice girls. And so we resorted to the only other coping mechanism seemingly available: internalization.

But of course, there are other factors that disadvantage women by promoting internalization, such as cultural expectations that women always be pleasant and oriented toward others, rather than themselves. In the talk to caregivers, Mate shares some obituaries that exemplify the values that we esteem in our society, which reinforce self-suppression. In one obituary, the husband of a 55-year-old woman, who died of cancer, praises her by writing:

“In her entire life she never got into a fight with anybody. The worst she could say was ‘phooey’. She had no ego; she just blended in with the environment in an unassuming manner.”

Blended in with her environment? Maybe if she had been able to say “F*ck” instead of “Phooey” she would still be alive today! Noting that repression of anger is a major risk factor because it suppresses the immune system, Mate quips, “I worry about really nice people!” In fact, in his book, he elaborates the profile of those diagnosed with ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease, and notes that the outstanding trait—without exception—is an extraordinary niceness and suppression of emotion.

There is much evidence that how we deal with anger has a crucial effect on our health. Mate cites one study done over 10 years ago that looked at 1,700 women over a 10-year period. Those who were unhappily married and suppressed their feelings were four times as likely to die as those who expressed their feelings.

I wish somebody had told me at a much earlier age that the role of “good girl” could be detrimental to my health. And by “good” I mean what society has, for so many generations, expected a woman to be—polite and nice, pleasing and agreeable. Though we’ve made progress in terms of acknowledging that women have needs beyond their assigned roles as mothers, wives, and help-mates, as the #MeToo movement revealed, much progress is needed in terms of women being permitted to speak up for what they want and to feel safe in setting boundaries.

It should be more widely known that over-identification with duty, role, and responsibility are major risk factors for illness. Maybe it’s time to question why so many more women are diagnosed with auto-immune diseases. For example, women are now three to four times more likely than men to get MS. Mate suggests that this is related to the increasing stresses faced by women who are still expected to fulfill their typical role of stress absorber in the family, as well as their additional roles in the work place, in the face of declining support networks and community. The fulfill-all-roles pressure that women face could be summed up in a 2015 BIC ad that read:

Look like a girl

Act like a lady

Think like a man

Work like a boss

Act like a lady

Think like a man

Work like a boss

Thankfully, the ad was pulled due to outrage over its sexist marketing.

On top of this pressure, women are still largely trained not to express their “negative” emotions. Yet, as Mate points out, “The role of emotion is to keep out that which is dangerous or unhealthy and allow in that which is helpful and healing. So we have anger and revulsion, and we have love and attraction.”

Perhaps it’s time for a Surgeon General’s Warning that says: Excessive niceness is dangerous for your health.

As I’ve been making my way through Mate’s book, I have been accessing some of the anger—as well as grief—that has been so tidily buried for God knows how long. It’s caused an existential crisis: Where does the real me begin and the social mask end?

It’s also provoked me to wonder if I would have developed thyroid cancer if a doctor could have told me at age 25 that repression of anger suppresses my immune system. I might have attempted to express–or at least coax out of hiding–the deep betrayal I felt at life for stopping me in my tracks in my prime. I might have been encouraged to yell out to God/Universe what I felt: “How could you let this happen at such a young age? Didn’t you know I had plans to save the world? To contribute to peace and justice and intercultural understanding?”

In fact, I’d been a “good” girl: I’d chosen service to world over service to self. I’d eschewed my interest in writing and literature, deeming International Relations to have more world-saving potential. (Excuse my ignorance, Elephant Journal!)

I wish I’d known at age 19, when being chased around the kitchen table of my university apartment by a man triple my age, that anger and the immune system have the same purpose: to protect boundaries. The immune system does its job of attacking foreign particles, while anger does its job of keeping out human invasions. In the throes of an outdated survival program, I was still trying to find a polite way to get this man out of my house.

Now multiply that scenario a few dozen times in my life, and just maybe it adds up to a very repressed immune system. Especially in light of the fact that suppressing responses to boundary invasions causes physiological stress.

Thanks to Mate’s book, I’ve made some amendments to my healing regime, which include:

1. Shamelessly venting to friends.

2. Buying a megaphone and arguing with God.

3. Saying “F*ck” as often as I like.

4. Absolutely, under no circumstances, blending in with my environment.

2. Buying a megaphone and arguing with God.

3. Saying “F*ck” as often as I like.

4. Absolutely, under no circumstances, blending in with my environment.

And of course, I haven’t forgotten the f*cking gratitude list. Because I’m a good girl.

~

AUTHOR: MARCI LAUGHLIN

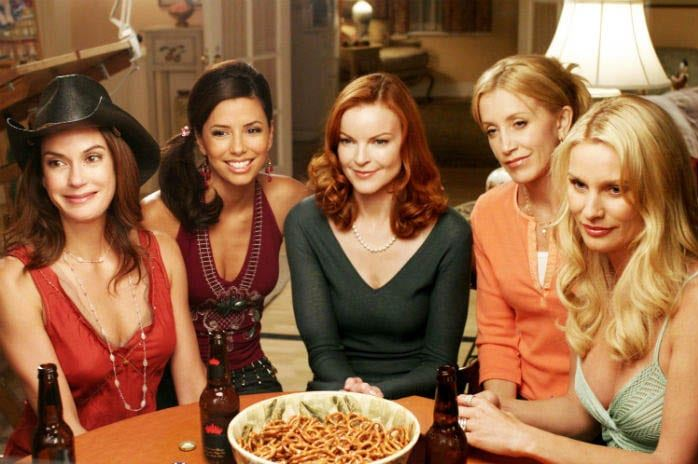

IMAGE: "DESPERATE HOUSEWIVES"/IMDB

No comments:

Post a Comment