*Part two of a seven-part series for Elephant Journal. Follow along at the author’s profile here. Order your copy of aah . . . The Pleasure Book here.

~

Marianne Williamson famously said, “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.”

She wasn’t kidding, scientifically speaking!

>> The atoms that make up your body were forged in the interior of stars and blasted into intergalactic space by a supernova.

>> If you unspooled the two meters of DNA coiled within each one of your five trillion (nucleated) cells and laid it end to end, it would span the solar system. That’s like going to the moon and back 26 thousand times. (Yes, you read that right.)

>> Your blood vessels stretched out would circle the earth two and a half times.

>> The four quarts of blood in your body (five quarts in a man) circulate through your body three times every minute and because your capillary beds are not all open at the same time, in one day travels 12,000 miles—four times the distance across the U.S. from coast to coast.

Without the least exaggeration, you are one of the most complex chunks of matter in the known universe and that’s just for starters. Your “power beyond measure” also includes the energy of your Light-body, as the following excerpt from Chapter 8 illustrates:

I first met Pattabhi Jois, the founder of Ashtanga Yoga, at Feather Pipe Ranch in the Montana Rockies on the edge of Helena National Forest, in May 1987. My roommate, Richard Freeman, and I drove out to attend a seven-day workshop. Each day, 15 of us lined up in two rows facing each other and went through the hour and a half primary yoga sequence while Guruji, as he was affectionately called, worked his way up and down the line adjusting people.

Pattabhi Jois was unremarkable in appearance with a round baby face, portly build, and a traditional Indian white dhoti neatly wrapped and folded about his waist. At first glance, you might mistake him for someone’s father. But at 72, his skin was smooth as milk chocolate, and he had the vigor and nimbleness of a man half his age. Quickly, with workman-like efficiency, he moved from student to student like a human blacksmith. His method was direct and forceful.

He synchronized the student’s breathing with a precise sequence of movements to heat the body like a bellows. Once the flesh glowed with sweat and became malleable, he applied pressure, using his whole body to bend and forge the struggling student into the prescribed position, or asana.

Each of us had our own particularly difficult asanas, and when one of us reached that point in the sequence, he would spend extra time, pressing us deeper into the pose whether we liked it or not. For me, it was baddha konasana, the Bound Angle pose. In this pose, you sit upright, hands clasping the soles of your feet with knees splayed open like butterfly wings. In the full pose, you turn the soles of your feet upward, as though opening a book, knees flat on the floor, and cantilever forward, placing your chin on the floor (in my case, a distant theory).

Each day when we got to baddha konasana, he would be on me, a foot on one thigh and a hand on the other, while his free hand pushed my head toward the floor. I fought back instinctively to keep my groins from being torn apart. “Aah…stiff-man,” he mumbled, annoyed, as he let me up and moved on.

His concept of the body and its anatomical limits was clearly different from mine. On the fourth day, I was, as usual, sweating, breathing hard, and struggling against him. This time, after pushing on me, he released his grip with his usual irritated grunt, but just as I inhaled with a sigh of relief, he thrust both my knees straight away to the floor with a whumph. It happened quickly and painlessly. I sat, stunned, bolt-upright with my hips completely open.

He had been setting me up all week like a cat toying with a mouse, waiting to pounce at the precise moment when my defenses were down. I have never been that deep in baddha konasana before or since, but the lesson was unforgettable: what I believed to be my physical limits was nothing more than my mental resistance. What really got me, though, was that he knew my limits better than I did.

In many respects, our Western concept of the body is still stuck in a Newtonian model of ball and socket levers and pulleys operating on a machine-like platform of biochemical algorithms. While our detailed anatomical dissections and biochemical analysis have allowed us to peer into the tiniest dimensions of our physical existence down to a molecular level, they have largely ignored the energetic dimension of our being—the élan vitale, the vital impetus—that mysteriously animates and pushes life to evolve toward ever greater levels of self-organizing complexity.

As William Wordsworth observed: “Our meddling intellect / Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things: / We murder to dissect.” We destroy the very life force we wish to study in order to place it under the microscope. But the situation is far worse. Western science does not even recognize the existence of a vital life force, let alone study it, as evidenced by the widespread dismissal and derision of vitalistic concepts. Such hubris is one of the consequences of having a deserted, dead cosmos for a cultural matrix.

For other civilizations, the existence of a vital force is commonplace. It is referred to as prana in India and qi in China. The closest translation in English is “spirit” from the Latin spirare (to breathe). It is intimately related to consciousness, intelligence, and breathing, which we will discuss further in Chapters 12 and 18.

Rethinking the body

The body is much more than we think. Our conventional Western view reminds me of old anatomy textbooks, which had transparent overlays so that as you turned the page, you first see the muscles, then the organs, nerves, blood vessels, and lastly the skeletal bones.

In medical school, we added a few more layers and looked at the tissues and cells, first under a light microscope and then under an electron microscope. Finally, we looked biochemically, down to the level of molecules in the DNA within the cell nucleus. Such is the incredible penetrating power of analysis.

The Eastern view takes a different approach. Asians didn’t do dissections, which in the days before refrigeration must have required some serious fortitude. Instead, they stepped back and looked at the body from a phenomenological perspective and tried to understand how it works by analogy to nature: the flow of water and wind, sun and moon, heat and dampness.

Both the ancient Indian yogis and the Chinese Taoists perceived channels—nadis and meridians—through which the vital energy of the body flows. The yogis added a few more overlays, subtle bodies called koshas, sheaths. Each of these sheaths was envisioned to be composed of increasingly finer grades of energy. The innermost sheath is known as Anandamaya kosha, the bliss body, or what I am describing here as the Light-body.

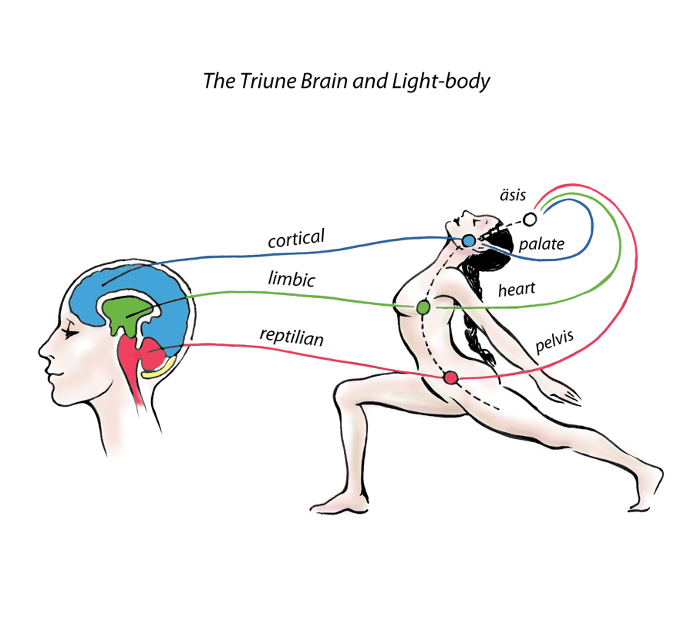

Figure 8: The triune brain and the four vital pleasure centers of the Light-body.

Consciousness is often compared to light because both illuminate. The Pleasure Prism describes how a pleasurable experience is refracted through the “optical” properties of the triune brain to illuminate the Light-body. Like a rainbow, there are no sharp edges that separate the different colors. Rather, we experience different frequencies and wavelengths of pleasure dynamically shifting and blending one into the other like the colors of oil on water. Thus, a pleasure encountered at one level quickly swirls into the others.

Hearing a familiar song on the radio can trigger strong emotions that mentally transport us back to our college days. Knowing we’ve helped someone with an act of kindness can generate warm emotional feelings. Indeed, we often find meaning and purpose in our lives through service to others, which can make giving more gratifying than receiving.

Physical pleasure is at the base of the prism for an important reason. All pleasures, regardless of where they originate, whether at an emotional, mental, or äsis level, quickly soak through to the physical plane and generate pleasant body sensations. It is ultimately these pleasant body sensations that define not only what feels good, but the very meaning (the experiential referent) for words such as good, beautiful, meaningful, and other positive attributions, which are simply different refractions of pleasure.

You can observe this for yourself. The next time you lay your eyes on a beautiful object, such as a mountain peak, a work of art, or an attractive person, notice that as your eye moves over the object, subtle pleasant sensations begin to stir and stream through your body. The same thing occurs when we are in the company of good friends, receive praise for a job well-done, or get goosebumps walking through a redwood forest. Every pleasure is ultimately experienced in and through the Light-body.

The Pleasure Prism is a luminous map whose secrets, if you know how to interpret them, can lead you back to the Garden of Eden from whence we came. Within each of the three chakras noted above, there resides a vital pleasure center which we will locate anatomically in Chapter 18.

When these three vital centers are fully activated and aligned, we spontaneously experience äsis, the clear white light of pure consciousness, which is nothing other than ecstasy, bliss, and equanimity.

The instant Pattabhi Jois slammed my knees to the floor into baddha konasana, and I was sitting bolt upright, it was like a light switch had been turned on. For a few moments, the gates had opened and everything, within my body and without, was extraordinarily vibrant and clear.

~

To find out more, please check out aah . . . The Pleasure Book trailer here.

AUTHOR: JIA GOTTLIEB MD

IMAGE: BARCELOS_FOTOS/UNSPLASH

This account does not have permission to comment on Elephant Journal.

Contact support with questions.