In the 21st century, compassion can often be perceived as weakness.

Our daily lives are organized around making money. Capitalist economies are governed by the maxims of individualism, competition, and profit, profit, profit.

Like me, I’m sure you have heard someone make the argument that to “make it” in the modern world, you have to toughen up. You shouldn’t show too much kindness, lest it be interpreted as weakness. You have to look after yourself before you look after others. In this dog-eat-dog world, not everyone can win, so our main concern has to be our own well-being.

But this is a hard philosophy to live by when we feel that something is missing—and it becomes nearly impossible to live by when we realise that ego is often the fuel for the pursuit of this type of success, leaving little space for compassion.

Compassion is the ability to display genuine concern for the suffering of others.

It is innate to human beings, but it has to be cultivated. It requires skill to integrate compassion into our actions, thoughts, and words.

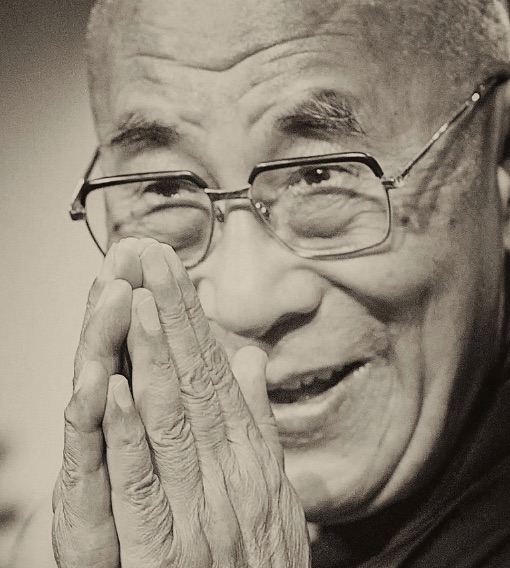

One of the greatest examples of compassion in today’s world is the nation of Tibet. In 1950, the military forces of the People’s Republic of China invaded this Buddhist country that sits on the Himalayan Plateau in the Land of Snows. In 1959, armed rebellion against the occupying forces broke out in Lhasa, the capital. Thousands of unarmed women congregated outside the Potala Palace to face the guns and to protect the 23-year-old Dalai Lama hiding inside.

Under the cover of darkness, the Dalai Lama escaped across the Indian border with thousands of his fellow refugees, dressed in a soldier’s uniform. He hasn’t stepped foot in his homeland since. Many of his fellow Tibetans were not fortunate enough to escape and suffered and died at the hands of the invaders.

One monk was released from Tibet several decades later, after years of being beaten, tortured, and terrorised by the Chinese. He was reunited with the Dalai Lama—and, upon seeing him, fell to his knees and apologised to his spiritual leader, humbly asking for his forgiveness.

“Brother, why do you require my forgiveness?” asked the Dalai Lama. The old monk replied that on one occasion, he had allowed his anger to overcome his love, kindness, and compassion for his oppressors. Once, he had allowed his suffering to blind him to the reality that his torturers were suffering and it was this that caused them to brutally persecute him and his kinsfolk. Just once.

This inspirational story is not unique. Many Tibetan Buddhists have not fought the Chinese, but have instead sought to understand them and to empathize with the difficulties of their situation.

How is this possible? How can the downtrodden in Tibet still feel love for their enemy?

The answer is rooted in the Buddhist principles of compassion (karuna) loving-kindness (maitri), and non-harming (ahimsa). In the Mahayana school of Buddhism, the supreme goal is not simply to become enlightened, to become an awakened Buddha liberated from samsara (the endless cycle of rebirth and suffering), but to actually delay breaking free from samsara in order to help others beings break free from suffering and guide them on their own way to nirvana. In other words, the highest virtue is to become a bodhisattva, loving every being as a mother loves their only child, and living in harmony with the supreme jewel of compassion, bodhicitta.

Last year, a Buddhist nun told me several stories about Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the master of Kopan Monastery in Nepal, who truly embodies this universal compassion and maternal love for all living beings. For instance, he often would stop at the side of the road and buy goats or cows to save them from the slaughterhouse, moved by their suffering. He saved so many that he eventually had to set up an animal sanctuary to house them all.

Rinpoche also used to own an old sock that he never washed. It was full of small lice which he happily allowed to feed on his ankle. One day, someone washed the sock by accident, and Rinpoche refused to speak to anyone in the monastery two days.

The most incredible story about this lama happened one evening when a novice monk entered his chambers and found him meditating without a robe. The lama’s back was peppered in dozens of mosquitoes ravenously drinking his blood. The lama didn’t flinch. After all, mosquitoes suffer the winds of samsara too, and he cared for each one of them as a mother cares for her only child.

We don’t all have the chance to live in the Himalayan foothills as we explore the way of compassion.

For those of us who work in high street shops and office blocks, sending emails to disgruntled clients and dealing with dissatisfied customers and spending hours commuting at rush hour, Rinpoche’s level of universal compassion seems like an impossible goal.

Life in a Western metropolis is a world away from the serenity of Tibet’s mountains. In the busy modern world, we just don’t have the time for bodhicitta. How can we show compassion when our boss flips out because we haven’t completed the mountainous stack of paperwork on our desk, or when that person behind us in the morning rush hour keeps beeping even though we’re all stuck in the same traffic, or when we’re running late and the girl in the coffee shop is being far too nonchalant in her preparation of our morning mocha?

This isn’t the way we expect it to be, so we begin to feel frustrated. We sense the tide of anger rising.

Where’s the compassion in all of these everyday moments? Where’s the awareness that everybody is suffering from the same stress, the same traffic, the same frustrations? If we could always remember the example of the Tibetan monk who tried to understand the suffering of his Chinese torturers, would we allow our own stress and suffering to govern our interactions with friends, colleagues, and strangers?

And furthermore, to cultivate universal compassion in the Tibetan mold, is it imperative to sacrifice the skin off our backs—our desires, needs, and daily lives?

No. The way to compassion is simply a matter of switching perspective, from self-cherishing to universal compassion. “If we look at happiness and harmony,” says Lama Ling Rinpoche, who once tutored the Dalai Lama, “we will find their cause to be universal caring. The cause of unhappiness and disharmony is self-cherishing.”

If our boss shouts at us, we feel criticised, threatened, and under attack. It makes us unhappy. It’s a human reaction to a familiar situation. A Tibetan Buddhist would say that this kind of reaction is produced by egotistical thinking and self-cherishing. Stepping out of the narrow world of self-concern, however, we can begin to try to see things from their perspective. Perhaps they had a bad weekend? Perhaps they had 30 emails waiting for them this morning? Perhaps they’re suffering? We can all empathize with these feelings. If we play with this new mindset, where then is last week’s frustration? Where’s the rising tide of anger?

Compassion is an experience of calmness. When self-cherishing is taken off the table, harmony pervades.

Tibetan Buddhists view themselves and the universe in a way unrecognisable to most Westerners. For them, a life committed to compassion makes much more sense than a life dedicated to ourselves.

There are three very important reasons for this.

First, there’s anicca, the cosmic law of impermanence. The pleasure we experience soon dissipates. The satisfaction we experience when we buy the latest iPhone is fleeting. The happy state of mind when we party with friends soon fades. Trees shed their leaves. Stars explode into supernovas. Even life itself is finite. Everything sooner or later ceases to exist. So, why pursue personal pleasure if it can’t last?

Second, there’s anatta, the doctrine of “no-self.” This is one of the most inscrutable of Buddhism’s teachings. The Buddha taught that there isn’t even a “self” to cherish. There is no ego to stroke, so to speak. When Buddhists meditate on the self or ego, they find that like everything in the universe, it too is fleeting. The self is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Who we are is actually where we are: the present moment. The person we think we are as we sit at our desk is not the same somebody as the person sharing lunch with friends, sitting in the morning rush hour, practicing yoga, or making a cup of tea. We fluctuate according to the changes in our environment. So, if we are part of a constantly changing stream of moments, where can the self be found? How can it be permanent? If the self isn’t permanent, who are we really trying to make happy?

Finally, there’s karma. Karma simply means “action.” It’s the idea that we all have the capacity to change the way we act here and now and that every positive action in the present creates positive results in the future; the same is true for negative actions. Just one act of genuine compassion can leads to positive results immediately—not just for others, but for ourselves. When we sympathise with a homeless person on a cold morning and buy a coffee for them, it makes them feel better. They have a smile on their face all morning. Seeing them sitting there smiling lifts the mood of people passing by. One positive act triggers a vibratory field of positivity. We’re also charged with positivity because of what we did, and because of this, all morning our interactions with our colleagues will be much more positive.

Compassion for others, paradoxically, really does benefit the compassionate person. It’s a win-win situation to put it in terms we Westerners do understand.

One of the Buddha’s last pieces of advice to his followers was simply to “do the best you can.” If we understand that we all suffer and adjust our thoughts and actions in accordance, we can create a space for caring, compassion, and kindness in our daily lives. If we cherish the well-being of others ahead of our own, we can all aspire to become everyday bodhisattvas committed to alleviating the suffering of others and our own.

“All the suffering there is in this world arises from wishing our self to be happy. All the happiness there is in this world arises from wishing others to be happy.” ~ Śāntideva

~

~

Author: James Pinnock

Image: Christopher Michel/Flickr

Image: Christopher Michel/Flickr

No comments:

Post a Comment