I’m a thinker. I’ve always been a thinker. I think analytically (sometimes), philosophically (often), critically (probably too much) and emotionally (almost constantly).

I draw inspiration for my thoughts from all manner of things around me: people on the subway, lyrics blaring through my headphones, magazine covers assailing me with visual stimuli, screaming sirens and noisy horns. All of it is a source of inspiration for stories and new ideas, and I tend to think of that as a positive force in my life.

These things are creative stimuli, to be sure, but I probably only notice about 10 percent of them. The other 90 percent of the places, faces and sounds around me go unseen and unheard; I miss them while I’m attending to the thoughts I’ve already conceived.

The popular cure for the ever-humming mind is said to be mindfulness. Learn to live mindfully, they say, and you’ll reduce stress, boost your creativity, improve your focus, and appreciate your surroundings. That all sounds great, but as a writer by trade and a thinker by nature, I’ve always had my qualms with this idea. Why would I want to quiet my mind?

There’s a certain paradox with which creative types must contend: An ever-buzzing mind is conducive to a bank of new, fresh ideas. Still, it’s no secret that creative types are prone to all of the things mindfulness is said to treat, such as anxiety, depression, mental illness and addiction. A study led by researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute confirmed that creative types are at a significantly higher risk for mental illness than the general population. Writers are particularly afflicted, being 121 percent more likely to suffer from bipolar disorder than their non-creative peers.

A person who practices mindfulness is consciously aware of what’s going on around her. When she eats, she concentrates on the taste, appearance, smell and texture of her food—not an exciting lead for a new story. When she walks to work, she pays attention to the feeling of her feet upon the pavement. She notices passersby, she listens to the sounds of the city—she doesn’t ruminate on ideas. When she lies down to sleep, she observes her breath as it goes in and out. She doesn’t analyze the day’s events or think about how she could do better tomorrow. She doesn’t prepare speeches or write monologues in her head.

Stefano Bernardi described his experience with mindfulness in an article he wrote for Medium.

“I’ve always been used to have my mind race with ideas, thoughts, to read as much as possible on every subject, just trying to learn learn learn and then regurgitate everything back into idea form … I used to get my best ideas and thoughts under the shower, in those 10–15 minutes where you don’t have anything else to do than think.”

Bernardi says that in training his mind to consciously observe his surroundings during the majority of his day, he became stressed. Constant brain activity had been a source of creativity, a spark of inspiration for new ideas—and without it, he was left feeling empty.

“The creativity that is generated by just thinking, and reading, and thinking, and trying to see how what you read can apply to other parts of your life, now just got completely lost. This led to a very stressful state, which was made even more stressful by the fact that I did not know what I was stressing about!”

Bernardi’s allegory resonates strongly with me. For those of us who love to think, mindfulness can be, well, boring. More than once, I’ve had the thought: Why would I want to stop my free-range thinking? Thinking is fun! My ability to think is my strongest attribute, why would I want to turn it off?

A huge part of living mindfully is knowing when to let your mind roam, and when to focus. I will never attempt to commute in a state of mindful awareness. I relish that time on the train, when I can be alone in a crowd, listening to my music or writing in my notebook, building upon the thoughts that have come and gone throughout the day. I will never be mindful when I’m on a run. Daydreaming while running is one of life’s greatest pleasures (and probably the reason I don’t view exercise as a chore).

At times, though, I have a toxic relationship with thinking. Like most creative types, I am prone to thinking too much. This can, and has, led to exaggerated emotional responses, depression and anxiety, and ideas and concepts I’ve valued for more than their proven worth.

There are times when it’s necessary to focus our minds for the sake of our mental health, and this is when mindfulness is helpful for the creative personality. When I’m having a conversation, savoring a delicious meal, drinking a glass of wine, or trying to fall asleep, mindfulness is necessary. In those situations, I need to savor the moment so that I don’t become disengaged, overeat, binge drink, or suffer from insomnia—all things I’m prone to do.

Mindful living doesn’t require constant observation, just as creative thinking doesn’t require constant introspection.

A well-trained mind (which is strengthened through regular meditation) can toggle between observation and activity, thereby harnessing its power to create. For me, this happy medium is where the inherent value of mindfulness lies: in its ability to optimize the hours we spend in thought, and to give us perspective when it’s time to observe.

Relephant Read:

26 Signs of a Creative Soul.

Author: Maggie McCracken

Editor: Emily Bartran

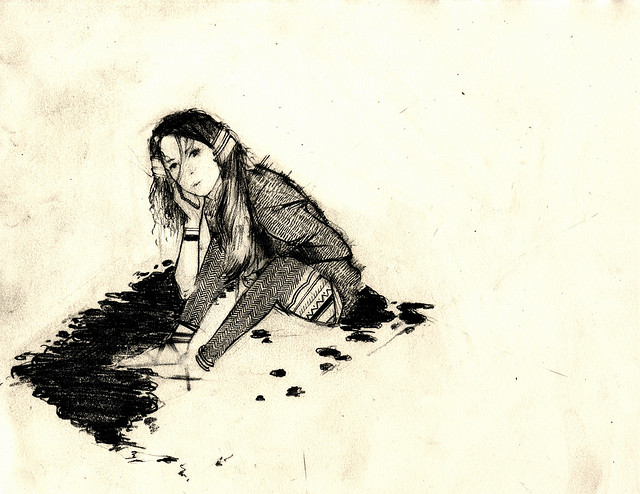

Photo: Mike Lay/Flickr

No comments:

Post a Comment